Gayatri Devi, Contributing Editor, North Dakota Quarterly

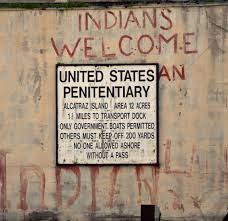

2019 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Native American occupation of Alcatraz island that lasted 19 months from 20 November 1969 to 11 June 1971. The occupation has been variously interpreted as an act of civil disobedience as well as the “first major instance of pan-Indian resistance in the twentieth century.” [1] Cherokee activist Chief Wilma Mankiller has described the occupation as “a spiritual reawakening of our people.” Indeed, as the tendentious power of the various hand-drawn signs broadcasting “freedom “and “peace on earth” on the smoke stack and the water tower of the Alcatraz prison, the notorious federal penitentiary, proclaim to this day, this daring act of a small group of Indians to establish the “Home of the Free Indian Land” upon the rock of a prison boldly frames the prison as an architectural and geographical metaphor for Native American belonging in the United States. It also frames the indestructible and inalienable freedom of the Native American spirit within the walls of their incarceration.

The 1969 occupation began when a handful of Native American students from the San Francisco Bay Area under the leadership of Richard Oakes (Mohawk) and Adam Nordwall (Red Lake Chippewa) decided to claim Alcatraz prison as a site to engage with Native American issues and activities. In the fall of 1969, the San Francisco American Indian Center had burned down in a mysterious fire leaving the thousands of Bay Area Indians with no place to congregate or to seek health and legal aid.[2] The large numbers of Indians in the Bay Area were a direct result of the 1953 Termination Policy of the federal government that decided to close down the Bureau of Indian Affairs, dismantle reservations and relocate Indians to urban centers. As Indian community leader Millie Ketcheshawno described the situation of the newly relocated Indians in the documentary We Hold the Rock, “We got off in a very poverty-type area in Oakland, and we got off, we said, oh my gosh, this is just what we came from.” LaNada Boyer, student occupation organizer at Alcatraz, described the twin feeling of betrayal and hope that the relocated Indians in the urban areas held: “We wanted a professional education and we wanted the assistance to be able to go to a university or any of the universities in the Bay area.” These betrayals and hopes gave a fresh momentum to the occupation and led to participation of large numbers of Bay Area Indians, particularly, students.

Federal government, at the time, was in the process of declaring Alcatraz as surplus land since it had been closed down as a prison in 1963. Indeed, a year after its closure, in March 1964, five Bay Area Sioux named Allen Cottier, Walter Means, Garfield Spotted Elk, Richard Mackenzie and Mark Martinez had gone to Alcatraz island and “claimed” it as Indian land under a little known provision of an 1868 Sioux treaty that “entitled the Sioux to claim surplus government land and facilities[3]” for their own. These first Indian claimants to Alcatraz had stayed only for an hour or so on the island, but in that short time, they had performed a ceremonial dance, and had written a proclamation justifying their right to take over Alcatraz as Indian land. The 1969 occupation followed the spirit of this first take-over of Alcatraz. Only this time, the occupation would last for nineteen months.

Even today, the original Alcatraz proclamation (1969) is pungent in its sardonic humor and mockery of proclamation rhetoric:

We feel that this so-called Alcatraz island is more than suitable for an Indian reservation, as determined by the white man’s own standards. By this we mean that this place resembles most Indian reservations in that:

It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation.

It has no fresh running water.

It has inadequate sanitation facilities.

There are no oil or mineral rights.

There is no industry and so unemployment is very great.

There are no health-care facilities.

The soil is rocky and non-productive; and the land does not support game.

There are no educational facilities.

The population has always exceeded the land base.

The population has always been held as prisoners and kept dependent upon others.

But during the 1969 occupation, Alcatraz would be physically transformed from a non-descript prison to a homeland for free Indians. The Native American occupiers of Alcatraz wrote poems, stories, proclamations and manifestos, established the radio station Radio Free Alcatraz from where activist-poet John Trudell conducted regular programming through Pacifica for and about Native American issues for Indian and non-Indian audiences, performed dances and ceremonial rituals, and instituted regular classes where Indian crafts, languages, and rituals were taught to a new generation of students and adults who had gone through the notorious boarding school system. These men, women and children, numbering around 400 at the peak of the occupation lived on the island, and they altered the façade of the prison forever with Red Power graffiti that remains to this day on the walls, water-tower, smokestack and ramparts of the feudal façade of the infamous prison.

In her simple poem “An Indian’s Song” (1969) written in Alcatraz, Dorothy Lonewolf (Blackfoot) envisioned a pan-Indian uprising set on the stage of the prison:

Stand firm, my brothers on the Rock

Do not despair!

Be brave, my brothers on the Rock

Our spirit’s there!

Walk tall, my sisters on the Rock

Stand with your men!

Grow fast, my children on the Rock

Learn our ways again!

O, Indians of Alcatraz

Lift up your eyes! [4]

The incantatory and imperative call of this song enshrines the transformative potential of an act of overt resistance. All the land that had been taken away from its people over centuries becomes a hard possession, or “Alcatraz, death buffalo of the sea,” [5] as described by another anonymous poet of Alcatraz, an indestructible foundation standing firm and unshakeable through the destructive storms of America’s nation building. At the peak of the movement, in the mid 1970s, the occupation gained much public recognition and momentum with hundreds of people sympathetic to the Indian cause visiting the island for short or longer periods of time. Efforts in San Francisco by supporters of the movement helped transport supplies to the island. Prominent actors and musicians such as Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn, Marlon Brando, Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Creedence Clearwater Revival lent their support to the movement and became its celebrity face. Trudell’s Radio Free Alcatraz broadcast began with Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “Now that the Buffalo has gone.” But the real faces and voices of the movement were the Indian leaders and activists, Richard Oakes, Dr. LaNada Boyer, Stella Leach, Shirley Guevara, Adam Fortunate Eagle, Grace Thorpe, Chief Wilma Mankiller, Leonard Garment, Brad Patterson, John Trudell, and the hundreds of Indian men, women and children who moved to take possession of the island in an assertion of their rights as the indigenous people of this land.

The second half of the occupation was riddled with internal conflicts between members; the departure of Richard Oakes, following the accidental death of his daughter on the island, further weakened the movement. The occupation of Alcatraz came to end in June 1971 when government forces removed the last of the remaining occupiers.

Alcatraz impacted Indians on and off the island for generations to come. Edward Willie, one of the young student occupiers featured in We Hold the Rock credits his grasp of his Native American identity to Alcatraz: “Before Alcatraz, I had no idea what an Indian was. Even though I had grown up in a reservation and I grew up around Indians, or earlier, in my younger years, I was around Indians, I didn’t know what an Indian was.” Millie Ketcheshawno, another occupier and student activist, noted that Alcatraz impacted all Indians, even those who did not participate in the occupation, “because it made them proud of who they are as Indian people.”

The occupation has often been described as the “cradle of the modern Native American civil rights movement.” Each year on Unthanksgiving Day, also known as the Indigenous People’s Sunrise Ceremony, and which coincides with the American Thanksgiving day, Native Americans and non-indigenous supporters gather at Alcatraz in a pre-dawn ceremony to commemorate both Alcatraz and the rights of indigenous people of North America. Native American protests at Mount Rushmore (1970), the Trail of Broken Treaties (1972), the occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (1972), the Wounded Knee incident at the Pine Ridge Reservation (1973), the Longest Walk (1978) are some of the more well-known of these Indian civil rights movements lit from the spark of the Alcatraz occupation. A flowering of Indian political and cultural renaissance that followed this occupation is examined in detail in James Fortier’s documentary Alcatraz is not an Island first broadcast on PBS nearly thirty years after Alcatraz.

In Chris Eyre’s pathbreaking Indian noir film Skins (2002), Rudy Yellowshirt, played by the Inuvik actor Erik Schweig goes to Mount Rushmore with a large can of red paint following the horrific death of his alcoholic brother Mogi played by the First Nations actor Graham Greene. Back in the Beaver Creek Indian reservation near the South Dakota/Nebraska border where they live (a fictional reservation modeled after Pine Ridge reservation), the liquor store that had fed Mogi’s alcoholism, and which Rudy had secretly set on fire, is being rebuilt with double the space and two drive-through windows. Rudy stands on top of Mount Rushmore, on the head of George Washington, and slowly tips the can of red paint over Washington’s head. The paint drips over Washington’s nose like a bleeding tear. The visual symbols of Red Power in the American landscape that suffused the smokestacks and water towers of Alcatraz have now with unerring aim crossed over into the realm of cinema, the realm of light and memory. Alcatraz lives forever.

~

[1] Rader, Dean. Engaged Resistance: American Indian Art, Literature, and Film from Alcatraz to the NMAI. University of Texas P, 2011. 9.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid, 8.

[4] Rader, 21.

[5] Rader, 23.

~

Gayatri Devi is a contributing editor to North Dakota Quarterly and an Associate Professor at Lock Haven University in Pennsylvania.